This is Mostly a Personal Reflection on Recent Travels

However, in my new book, Staying in the Game: Leading and Learning with Agility for a Dynamic Future, I wrote about several themes that contribute to successful leaders’ ability to continue to learn and adapt. A key aspect of this capability is a clear sense of their Meaningful Identity, or what values and experiences give meaning to their lives and work. I wasn’t expecting to discover more about my own Meaningful Identity on a recent trip to Norway. Read on if you are interested to learn more!

Our time in the Laerdal area of Norway this fall has opened up a new dimension of Meaningful Identity that I wasn’t expecting. While I was excited to spend time in the land of “my people,” I had no big agenda about tracking down relatives, searching local records, or walking graveyards. I’m no genealogist, and while I find it interesting, I don’t have the patience for doing a lot of roll up your sleeves kind of research. That all changed when I mentioned to the owner, Knut Lindstrom, of the Lindstrom Hotel where we stayed in Laerdal, that my great-grandfather was from the area.

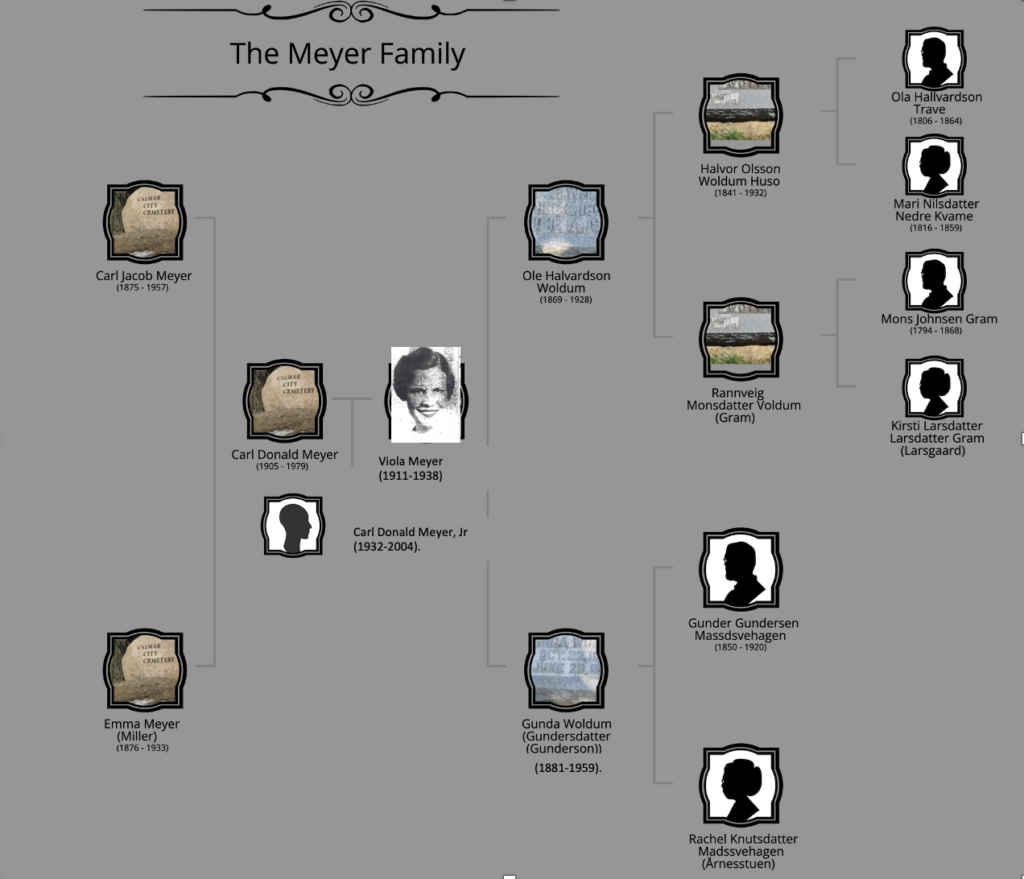

Me and Knut Lindstrom with the Laerdal Bygdebok

He said I might be interested in a book he had that could be helpful, the “Bygdebok.” I learned that in Norway, family names are the names of the farm(s) the family is from; every area has one of these books (more on this here). They are records of who lived at which farm in locations across Norway. He brought out the book and said I was welcome to borrow it, so I spent half the night pouring over it and identifying the farms where both my great and great-great grandparents (on my dad’s side) lived.

Interestingly, because my great-great-grandfather began on the Trave farm but later moved the family to the Voldum farm, the name they came to America in 1885 (settling in Decorah, Iowa, where I was born) with was Woldum (how it was pronounced and written down by the immigration folks, and became the family name for evermore in the US).

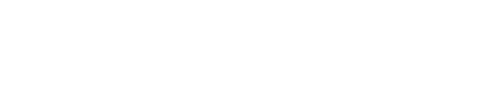

My Family’s Norwegian Ancestors

My great-great grandparents Halvor Olsson Woldum Huso (1806-1864) and Rannveig Monsdatter Voldum (Gram) brought their one daughter and five sons, including my great-grandfather Ole Halvardson Woldum over in 1885. According to the records in the Laerdal Bygdebok, Hallvard and Rannvieg had “1 horse, 3 cows, and 16 small animals.” The Google translation may be wanting here, but it also says, “There was little pasture, and the farm was used for rustling [what is that?!]. On the other hand, there was enough forest for domestic use. The garden was well cultivated and lightly used by the standards of the time. In 1875, the tally was: 1 horse, 4 cows, 3 young cattle, 20 sheep, and 20 goats. Then, you could harvest 4 barrels of barley and 5 barrels of potatoes. In 1876 Hallvard sold the farm and moved the family to Voldo.”

They don’t look so dangerous now, but get them backed into a corner stomping at you . . .

We located two of the family farms (Trave (Trao)/Atti-Trave and Voldum) thanks to Knut Lindstrom. We hiked up to them with guidance from the church visitor center, crossing a few active farms and their resident sheep.

![]()

![]()

We had a comical run-in with four of the sheep, whom we accidentally cornered between fences and in front of the gate we needed to pass through. These sheep had big horns and were clearly agitated at our presence. One came to the front of their little pack and stomped (trying to scare us off?). I was a little worried that they might try to rush us, so we backed off and hung out down the road, hoping they would find their way past us. Instead, they just lay down on the path. After about 20 minutes of this, I called the church visitor center and described our embarrassing standoff. He laughed and said the sheep were probably more afraid of us than we were of them, and it would be fine to walk through them. As we started moving, they got up and began hurrying past with terror in their eyes. I felt so bad for all of them and hope they quickly got back to enjoying their quiet lives munching on the mountainside. This is what happens when two “tough” city girls head into the mountains of Norway!

We had a comical run-in with four of the sheep, whom we accidentally cornered between fences and in front of the gate we needed to pass through. These sheep had big horns and were clearly agitated at our presence. One came to the front of their little pack and stomped (trying to scare us off?). I was a little worried that they might try to rush us, so we backed off and hung out down the road, hoping they would find their way past us. Instead, they just lay down on the path. After about 20 minutes of this, I called the church visitor center and described our embarrassing standoff. He laughed and said the sheep were probably more afraid of us than we were of them, and it would be fine to walk through them. As we started moving, they got up and began hurrying past with terror in their eyes. I felt so bad for all of them and hope they quickly got back to enjoying their quiet lives munching on the mountainside. This is what happens when two “tough” city girls head into the mountains of Norway!

The family farms of Trave and Atti-Trave are just above the Borgund Stave Church. When my family lived there, apparently, the vicar of the church also lived on the property.

Borgund Stave Church

Trao/Trave Farm

Pamela at Atti-Trave Farm

Adding even more delight to this discovery process, when we came upon the Atti-Trao/Trave farm and the inviting note to enjoy the picnic table (see photo) and view, we saw a couple already taking up the invitation. This is where my great-great-great grandfather, Ola Hallvardson Trave lived in the early to mid 1800s, and where my great-great-grandfather lived before moving to the Voldum farm. We were hesitant to interrupt their quiet conversation, but they were both so warm and welcoming when we did. We learned that they were from Holland and had recently sold their home, quit their jobs, bought a camper van, and were traveling around Europe, taking advantage of the time to explore and discover their “what’s next.” They were really interested to hear about my family’s connection to the farm, too. We talked a bit longer,

Pamela, Bart, and Carol

shared our travel plans and tips for the next few days, including taking the scenic Flamsbana train out of Flam. We kicked ourselves that we did not exchange more information, as it was such a lovely connection. The universe took care of us a few days later when, after settling into our hotel in Bergen, we were walking through the Fish Market, deciding where to eat dinner, when a tall blonde man jumped in front of us and said, “Hello!” It was one of the men we met at the Atti-Trao farm! It turned out he took us up on our suggestion to ride the train (and had even seen us through the window passing the other direction back to Flam the day before) and had continued on his own for a few days to explore Bergen while his partner stayed back at the camper van. He had just sat down for dinner and happened to look up as we were passing by. We didn’t delay introducing ourselves this time and invited ourselves to join him. As we sat together, we were all in awe of the mystery of the universe putting us in each other’s paths during such important times in our lives. How I was searching for family roots, thinking about my family’s story of transition, while Bart and his partner were on an adventure and embracing this time of transition in their lives—discovering how their story is unfolding (you can follow their adventures on Insta here).

Pamela at Voldo Farm, home of Gunda, Ole, and their children before migrating to the US

What a wonderful new connection as I continue to digest what it means to spend time here in Norway. I am so grateful to immerse myself in the natural beauty of the area and the culture. I feel enlivened in a way I don’t fully understand and can’t yet describe. On one level, this exploration and the hike to the family farms have connected me to my roots I didn’t even know I was missing and some ineffable essence of who I am. On another level, with only the facts and without the stories of the family members who lived here, I am left with so much more to wonder about.

For example, I find it interesting that Norwegians derived their family names (their identity, literally their identifiers) from a place, while other cultures derived them from their profession. Perhaps because, for Norwegians, they were one and the same—where you lived dictated what you did.

I may do more digging, and I don’t know that more facts are important to me. This experience and exploration have me thinking about what endures after all who knew our stories are gone. What endures after our personal artifacts have faded and only the facts are left (where we lived, what we did, who gave birth to us, how many chickens and sheep we owned or didn’t)? And what will those facts mean to anyone with enough curiosity and means to discover them? And what is finding home? Is it hiking up to the family farm that your great-great-grandparents worked? Is it discovering the place where you feel comfort, love, and meaning? Is it finding and constructing a story from the facts, relationships, and experiences of our lives?

I am wondering about what prompted the family’s big transitions—first from one farm to another and later to a new country altogether. One possibility is that the regular avalanches up in the higher elevations of the Trave/Atti-Trave farms prompted the first move. Or perhaps because Voldo farm had more arable land to grow crops, which was not possible on the steep rocky terrain of the other farms. Some of the locals I talked to said that the terrain simply could not sustain many of the larger families (reports vary that between 2 and 7% of the country is arable).

I also wonder about the stories they heard about coming to America and what promise the new life held for them. What did it take for an entire family to pack up and leave all they had known, their relationships, and their ties to the land—knowing they would likely never return? And this is prompting me to think about all of the immigrant stories we have in our lives. Anytime we ponder a transition from the known to the unknown, we risk losing comfort and stability; even if it is untenable in some way, it is known to us. What story do we construct about the possible new life that might await—in new learning, moving to a new town, job, relationship, or other significant life transitions—both planned and unplanned?

I am thinking anew, too, about the work of the Albany Park Theater Project (the youth arts organization I have long championed) and the stories they collect, explore, and share, and the importance of not only the sharing but the process of remembering, reconstructing, and telling these stories. With all of the new immigrants crossing our borders, the focus for those of us who have been here for some time is often on the concern for our communities’ ability to accommodate so many newcomers, the potential strain on resources, or even a fear of “the other” (and we have grappled with these issues in the US from our earliest days). As we continue to debate and respond to these issues, we must do it humanely and in a way that honors all of our stories and quest for Meaningful Identity. Whether our migrations happened generations ago or more recently, they were prompted by shared compelling forces, risks, fears, sacrifices, hopes, and dreams.