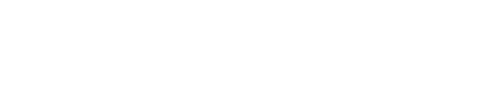

How Fit is Your Business? Part 2: Flexibility

In Part 1 of this series, we’ve already learned that keeping your business “Fit” will keep your moves agile. Agility, along with adaptability and resourcefulness, are the keys to maintaining our next business performance indicator: Flexibility.

Have you developed the competence and capacity to adapt when things don’t go as planned?

Remember, strength and flexibility are interconnected. The more flexible you are physically the more access you have to the strength in the entire length of your muscles. However, too much flexibility without strength can lead to instability.

In the gym, if we only concentrate on strength, our muscle fibers shorten and limit our flexibility and range of motion (you’ve heard of the term ‘muscle-bound’), which can lead to injury.

In business, flexibility means being able to use your core strengths to adapt to and respond effectively to both challenges and opportunities.

This is the essence of what I have come to call The Agility Shift. Without the capacity for agility, no business can sustain its relevance or results.

Practice Flexibility

Just as our bodies need intentional practices to maintain flexibility, so do our organizations. Without intention, the muscles in our bodies and our organizations will atrophy.

We can all name brands, businesses, even entire industries that allowed their success to lull them into believing that they did not need to continue to adapt and innovate. Most athletes know they are only as good as their most recent competition. This knowledge motivates them to jump right back into the gym soon after a successful competition.

Continuous training means you are always pushing performance to the next level, no matter whether you are working out or planning the future of your organization .

How Can You and Your Organization Become More Flexible in 2018?

I highlight several ways highly flexible and innovative organizations stay that way in my books From Workspace to Playspace and The Agility Shift. It starts with a mindset shift and extends to shifts in the ways you work and do business, as well as how you implement and use highly adaptable systems and processes.

One of the best ways to improve collaboration and flexibility only takes a few minutes. Try it the next time you meet with your team. Kick off your meeting with a quick improv or agility exercise, here is one of my favorites.

One of the best ways to improve collaboration and flexibility only takes a few minutes. Try it the next time you meet with your team. Kick off your meeting with a quick improv or agility exercise, here is one of my favorites.

Where and how do you and your team “work out” to maintain your strength and flexibility to meet the next opportunity?