Or Eight Ways GenAI Can (and Cannot) Enhance Your Leadership Development Strategies

Generative AI (GenAI) has revolutionized everything from customer service to software development. Referring to platforms, apps, and other new tech that can generate images, text, and even write code, GenAI enables businesses to be nimbler, more responsive, and offer greater customized solutions than ever.

Slowing Down to Go Fast in the World of AI

Before you start downsizing your learning and development team or abandoning your mentoring and coaching programs, this article will help you slow down and assess the value and limitations of GenAI strategies for learning and leadership development.

One of my favorite questions to ask the leaders I have worked with over the last twenty-plus years is, “Think of an experience that changed you in a significant way.”

In response to this prompt, I have heard stories that include a leader who received the challenging feedback they needed to hear from a mentor at just the right time, a leader who gave a stagnating team member a new stretch assignment, a former professor who helped a CEO sort through a complex ethical dilemma, and a friend who was a sounding board in a way that helped her decide in a high-stakes situation with competing priorities.

Other emerging leaders have described being thrown into new situations where they discovered or developed a talent or capability they didn’t know they had or a breakthrough that emerged in a safe yet challenging learning environment. I have also witnessed leaders who were able to rise to the occasion and effectively respond to the unexpected and unplanned by connecting with a critical resource via a trusted partner who generously engaged their network.

These stories of impactful and transformative experiences share a common thread: they were relational, not transactional, just like leadership. Transformation and growth do not happen in a vacuum; they occur over time, through iterations of experimentation and feedback, and in relationship with colleagues, trusted advisors, and within the context and culture of their organizations and wider business ecosystem.

Technology cannot replace the relational interactions at the heart of leadership development and effectiveness.

If you work in learning and leadership development, I don’t have to remind you that:

- Leadership is Relational, Not Transactional

- Leadership Development is Iterative and Happens Over Time

- Leadership Development is Contextual and Cultural

For example, in my work with leaders, we start from the premise that learning about Embodied Agile Leadership (EAL) is not the same as embodying agile leadership. Leadership development requires active engagement in what I call the Three C’s: Competence development, Confidence-building, and the Capacity to perform effectively in a wide range of unexpected and unplanned situations.

In the excitement over GenAI’s capabilities and benefits for learning and leadership development, we mustn’t lose sight of the role and value of human interactions at the heart of leadership growth and development. These same interactions and the trust and understanding they foster are also at the heart of how we make sense of complex situations, get things done, and ultimately generate and deliver value for customers and stakeholders.

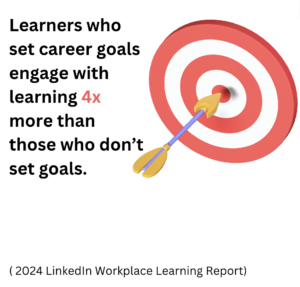

Be Responsive, Not Reactive

It’s good news that technology will continue to evolve and become even better at recognizing patterns, analyzing data, and generating content. As learning leaders, we are responsible for evolving with the technology and guiding our colleagues and clients on GenAI’s value and limitations in supporting leadership impact and success.

Rather than react out of our initial excitement or existential fear, we can respond in a way that engages and partners with all available resources to support leaders’ success. With this in mind, here is my high-level overview of some ways learning leaders can tap generative AI and along with insights into ways your role as a living, breathing, relational human being is more important than ever. I began this reflection by asking ChatGPT: How Can Generative AI Enhance Agile Leadership Development?

What follows are eight headlines inspired by the AI-generated list, along with my human-generated response, inspired by several conversations with learning colleagues and clients about the role that learning leaders, including peers, mentors, coaches, and learning and development professionals, can and must play to ensure leadership success, particularly in a fast-paced, uncertain present and for a dynamic future:

Eight Ways Gen AI Can (and Cannot) Enhance Your Leadership Development Strategies

- Creation of Personalized Learning Plans

- GenAI can analyze individual leadership styles, strengths, and areas for improvement based on performance data.

- It can also generate personalized learning plans that cater to each leader’s specific needs and preferences, ensuring a more targeted and effective development journey.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners: can understand the nuance and complexity of each leader’s role and current context in a way that data analytics simply cannot. Ideally, leaders partner with a coach or mentor who can serve as a sounding board and guide to interpret assessment results and collaborate to refine AI-generated learning plans. This way, the leader has a learning and action plan relevant to their current context and business goals. Additionally, they have a human being with whom they can interact to brainstorm, troubleshoot, and reflect on their progress with accountability. Leaders seeking to develop leadership agility need a trusted partner to help them stretch and adapt as conditions change.

- Simulation and Scenario Training

- Through generative AI, realistic leadership scenarios can be simulated, providing leaders with a safe environment to practice decision-making and problem-solving.

- Leaders can engage in virtual scenarios that mimic real-world challenges, helping them develop agile thinking and decision-making skills.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners can help refine and maximize the value of scenario-based training, which can be highly effective in assisting leaders in building their confidence in VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) situations. To make the most of these experiences, leaders can partner with a coach, mentor, or peer to refine their agile leadership development goals before the learning experience. After participating in the scenario, leaders can partner again to reflect on their experience, including what they did well and areas for improvement. Leaving this to AI removes an important aspect of leadership development critical to building competence and confidence. Learning professionals and trusted peers can also help leaders make connections between their scenario-based learning and the high stakes of their current reality, resulting in actionable insights.

- Continuous Feedback and Coaching

- GenAI can offer real-time feedback on leadership behaviors, communication styles, and decision-making processes.

- Automated coaching systems can provide constructive insights and suggestions for improvement, enabling leaders to iterate and adapt their approach in real time.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners are critical in understanding the complexity of the leaders’ current context and adapting any AI-generated suggestions. A learning partner can also be a sounding board to help leaders prioritize actions that will make the best use of available resources and deliver the greatest value to their stakeholders. Learning leaders can grasp the subtleties of organizational culture, industry-specific challenges, and individual nuances that are challenging for AI to comprehend fully. They can also suggest more learning and development resources based on their in-depth knowledge of the organization and industry. Trust is crucial in leadership development, and the human element plays a significant role in establishing and maintaining it.

Coaches can build this trust with leaders, creating a supportive and confidential space for discussions.

- Data-Driven Decision Making

- GenAI can identify trends, patterns, and correlations related to leadership effectiveness by analyzing large datasets.

- Leaders can leverage these insights for data-driven decision-making, enhancing their ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners help leaders make sense of data analytics within the organizational context and culture and can support ethical decision-making. In a fast-paced environment, starting with AI-generated suggestions based on large-scale industry trends or other benchmarks can be helpful. These suggestions, however, are only a starting point. As leaders engage with these suggestions, they must prioritize growth strategies based on their current capacity, available resources, and most pressing goals and accountabilities. In partnership with a peer, mentor, or coach, this process is an opportunity to increase self-awareness and identify biases and blind spots in the decision-making process. Relational decision-making also fosters accountability, the formation of trusting relationships to draw on to make sense of complex situations and competing priorities, and the reduction of uncertainty.

- Adaptive Leadership Development Programs

- GenAI can continuously assess leaders’ progress and adapt the development program based on their evolving needs and the changing business environment.

- This adaptability ensures that leadership development remains relevant and aligned with the organization’s goals and challenges.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners can help foster the learning agility at the core of sustained leadership agility. GenAI platforms can learn your leaders’ priorities and refine and adapt their suggestions and guidance. However, trusted learning partners with a deep understanding and relational ties across your organization and business ecosystem are best positioned to help leaders identify and engage their networks to identify the stretch opportunities best suited to develop learning agility.

- Natural Language Processing for Communication Enhancement

- GenAI, particularly using natural language processing, can assist leaders in improving their communication skills.

- It can analyze written and spoken communication, offering suggestions for clearer and more effective messaging and fostering better collaboration within agile teams.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners know that only humans who have lived the experiences and have gained their wisdom through mileage can inspire through authentic personal stories. They are also adept at weaving their unique narratives into one-on-ones and coaching sessions to create genuine connections and foster trust. Situationally, they can also understand and respond to the complexity of human interaction and nuances in tone, body language, and emotion that are essential for effective communication. By incorporating authenticity and personal stories, learning professionals and partners create a safe space for individuals to explore their communication styles, address challenges, and develop strategies for more impactful interactions. This human touch adds another layer of empathy and understanding to foster meaningful communication and build strong, collaborative relationships.

- Predictive Analytics for Leadership Success

- Generative AI can use predictive analytics to identify potential leadership success factors and areas of improvement.

- AI can analyze historical leadership data and success metrics to provide insights into the traits and behaviors contributing to effective leadership in an agile environment.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners can ensure that AI-generated prescriptive approaches and assessment results are held lightly. The best AI metrics can do is describe various behaviors that correlate with a range of outcomes. It is important to remember that these benchmarks do not necessarily prescribe one-size-fits-all solutions for any single leader or the complexities and competing priorities of their context and accountabilities. For this, leaders need a trusted thinking partner, coach, or mentor who can serve as a sounding board.

- Customized Content Creation

- GenAI can automate and customize the creation of learning materials, generating content such as quizzes, case studies, and simulations.

- This accelerates the content creation, ensuring a constant supply of fresh and relevant materials.

Living Learning Professionals and Partners understand the difference between providing content that helps leaders learn about something and developing the Competence, Confidence, and Capacity to draw on new learning in high-stakes and complex business environments. To develop these Three C’s, leaders need humans adept at facilitating group discussions, fostering collaboration, and managing group dynamics. Live experts can create a safe and interactive learning environment, encouraging open communication and collaboration among leaders. In addition, agile leadership development often requires real-time adjustments to learning strategies and interventions. Learning professionals can quickly adapt their real-time guidance in response to team dynamics, emerging situations, or learning opportunities. Live facilitators can also key into individual needs to inspire and motivate leaders, fostering a positive mindset and a commitment to continuous improvement. These interactions provide meaningful encouragement through shared stories, personal experiences, and role modeling, which even the most sophisticated AI platform is challenged to replicate authentically.

While AI can enhance many aspects of leadership development, combining AI resources and live learning experts creates a more holistic and effective approach. As you continue to evolve your leadership development strategies, the key is to engage technology for data-driven insights and efficiency while preserving the human touch for the complex interpersonal dynamics and individualized and critical context-specific elements of agile leadership development.

Link to the Original Article on LinkedIn

This is the 3rd installment of Pamela’s Summer of Learning Series.

This is the 3rd installment of Pamela’s Summer of Learning Series. Success Story:

Success Story:  Why It’s Important to

Why It’s Important to  This is the 2nd installment of Pamela’s Summer of Learning Series.

This is the 2nd installment of Pamela’s Summer of Learning Series. Here are a few questions to get your curiosity wheels turning

Here are a few questions to get your curiosity wheels turning Progress, Not Perfection

Progress, Not Perfection

enterprise develop their learning agility competence, capacity, and confidence.

enterprise develop their learning agility competence, capacity, and confidence.