Agility is perhaps the most essential capacity for organizations today. A recent study by MIT showed that agile organizations grow revenue 37% faster and are 30% more profitable than non-agile companies (Glenn, 2009).

So what enables organizations to be agile?

The two most salient factors influencing organizational agility, according to a comprehensive review of research done in the field (Bottani, 2010) are:

1. Employees role and competency in the company

2. Technology: Virtual enterprise tools and metrics and the adoption of information technology systems

What does this mean for your learning and development strategies?

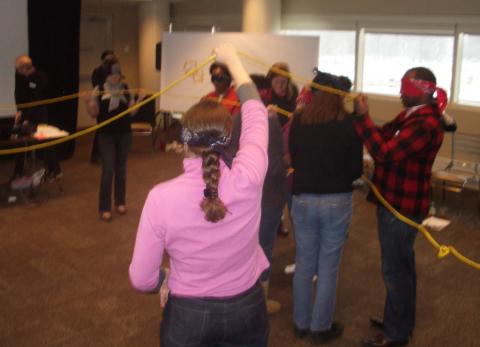

Confidence and Competence Development. Every organization must have an explicit strategy to help individuals, workgroups and entire divisions develop the capacity to effectively improvise in response to the unexpected and unplanned, as well as to spot and respond to emerging opportunities and trends. This involves more than improving communication and resource sharing, though these are also key. It means providing significant experiential learning opportunities for individuals and groups across sectors to develop their competence and confidence in thinking on their feet, acting in the moment and effectively drawing on all available resources—human, material, technological and intuitive.

Technology Infrastructure. Agility also demands that all organizational participants have the tools and resources to quickly access the organization’s knowledge network and relationships. A simple knowledge management system is no longer sufficient for agility; individuals need to be able to quickly access the people and capacity of the organization, not simply search decontextualized bits of data.

Research also shows that people need more than just awareness and access to their knowledge networks; they need relational connections and context to effectively use the network (Cross and Parker, 2004). Learning and development approaches that combine the development of social capital, along with awareness of and access to the wisdom and experience of the network are thriving. Creating a technology infrastructure that provides the stability and flexibility for responding to emerging opportunities, along with enhanced confidence and competence in improvisation is an unbeatable strategy for creating the agile organization. New technology like Artificial Intelligence can go a long way in meaningfully contributing to building this learning and development infrastructure.

What strategies are you using to enhance agility in your organization?

Bottani, E. (2010). Profile and enablers of agile companies: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Production Economics, 125, 251-261.

Cross, R., & Parker, A. (2004). The hidden power of social networks: Understanding how work really gets done in organizations. Cambridge: Harvard Business School.

Glenn, M. (2009). Organisational agility: How business can survive and thrive in turbulent times: Economist Intelligence Unit.