Reprinted From SNL Writing News: Writing information for DePaul University’s School for New Learning faculty and staff

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

1. What inspired you to write this book?

I discovered the power of permission during my research on adults’ experiences learning to improvise, and which I wrote about in my last book, From Workplace to Playspace (Jossey-Bass, 2010). Improvisation initially feels very risky for most people and when someone (or several people) help co-create a safe, dynamic space for risk-taking, the chances that real learning and transformation will happen greatly increase. When people feel they have permission via someone else taking a risk and not being ridiculed (or even receiving positive feedback), a wonderful shift starts to happen: people start generating more ideas, being more of themselves and having more fun (which is why we made this the subtitle of the book). This concept extends to all areas of adult life, especially at work, where we often gauge our behavior based on the social cues around us. We may hear people talking about the importance of risk-taking, playing around with ideas and being authentic, but unless people actually see the behavior in action, they may not feel they have actual permission to do so.

The concept of permission and the role of the permission-giver resonated a lot with readers and workshop participants as I traveled the country talking about the book, as well as with, graphic facilitator, Brandy Agerbeck (with whom I have collaborated often over the years). Brandy is very interested in giving people permission to draw and to explore their capacity for visual thinking and communication. After an initial informal conversation to play around with the idea of the book, we decided to meet to brainstorm a long list of permissions we sometimes need to remind ourselves to give, take and get. These include permission to be silly, use our whole bodies, question, take a break and many more.

2. Permission was a collaborative effort with graphic facilitator Brandy Agerbeck. Can you tell us a little bit about the co-creation process?

After brainstorming our initial list of about 35 permissions, Brandy and I met a few times to discuss the dimensions of each permission and help each other think as playfully and expansively as possible about each of them. This served as inspiration for me to begin writing and Brandy to begin playing with various images that reflected and/or evoked each permission. While we each worked to our strengths (me, writing and Brandy, creating the images), we chose to call ourselves co-creators, rather than the more traditional titles of author and illustrator. We felt that separate titles didn’t fully honor how we worked together, which was very collaborative and co-creative. We soon discovered that Amazon does not have the option to list yourself as a “Co-creator”, so you will see us both listed as authors, which doesn’t accurately reflect our collaboration either. We are clearly breaking new ground here.

3. What was your process for writing, revising, and editing this book? For example, did you work with an outline, did you experience writer’s block, did you have outside reviewers, how long did it take, how many drafts, any major changes to organization/structure of the ideas/sections?

In terms of our individual processes, I call myself a “turtle” when it comes to writing. I like to write very first thing in the morning, at least five days a week, though often I only write for 30-45 minutes. I gave myself a quota over the summer of drafting three permissions a week. Every Friday I would send the week’s writing to Brandy, who would read the permissions, make notes to provide feedback, and begin working on the images. If I am a turtle, Brandy is more of a rabbit in her work process. She likes to work in bursts, so would often wait until she has 10 or 12 images to start working on and then hole up in her studio to work on her drafts. We would then meet in person go through our drafts, each giving the other feedback and continuing our brainstorming, which would send us back to work on the next iteration individually. Along the way we shared sections with trusted readers for feedback, and also decided to cut a few of the permissions that either seemed a bit redundant, or just didn’t excite us as much as the others.

I can’t say I experienced writer’s block per se, because of my discipline to write every morning. Just like exercising when we don’t feel like it, or going to work when we might rather be doing something else—writing is a discipline. I would sometimes move on to work on another section of the book, if nothing was coming to me thinking about the section in front of me, and I always wrote something each day. We continued this iterative process through to the end of the summer and by early September agreed that we had a solid draft of the book. At this stage we moved into production mode.

4. What made you decide to forgo the traditional publishing route and use self-publishing?

There were two main reasons we chose to self-publish this book 1) Speed to publication and 2) Creative control. My first two books were represented by agents and published by major publishers. These were generally good experiences and certainly useful in building my credibility as an expert in the field of creativity and organizational change. At the same time, with traditional publishing, there are a lot of other stakeholders in the process from the agent, who wants to choose a publisher who offers the biggest advance (not always the best choice for any given book) to the marketing department, who may have the final say on your title and cover design (which might have little to do with the actual contents of the book) and list price. Brandy and I had a very clear vision of what this book would look and feel like, as well as our target audience. We did not want to get caught up in convincing others of the value of our vision, nor did we want to slow the process down. If we had gone with a traditional publisher, we would likely be looking at a publication date of up to a year later than when we were actually able to get the book out. We both wanted to have it out quickly to build on the momentum of the Workplace to Playspace readership and also to have it out in time for holiday gift-giving. By self-publishing via Amazon’s CreateSpace service, we were able to control all of the creative choices, the cover price and the timing.

5. What specific publishing services did you use from Amazon? Would you self-publish again? If so, would you purchase any additional services, or do without any of the services you used this time?

We were lucky to have between us many of the competencies necessary to take the book from conception through to publication. I had a lot of knowledge about the overall production and distribution process and Brandy had the skills and talent to do the full layout with images, design our cover and properly prepare the pdf document for uploading. We did pay for light editorial services to catch typos, unintended word repetition, etc.

We would both definitely consider self-publishing again. If I were not working with someone with a design background, I would consider using their design services, and would definitely use the editorial services. Both were more cost-effective than hiring these separately from outside vendors, and we were happy with the overall quality and efficiency of the process.

6. Do you have any words of advice or tips for aspirant writers?

Writing Advice: Think of writing as a discipline. Don’t wait for inspiration or until you get the perfect writing space, your house is clean, or you get one more credential. Pick a topic and write.

My two cents on publishing: Before you decide whether or not to self-publish or to explore traditional publishing, you need to be able to answer the question: what do I hope to accomplish with this book? If your primary goal is to get something out quickly to a target audience with whom you already have a relationship, self-publishing may be your best option. If you really want the additional credibility and visibility that comes with a mainstream publisher, and are willing to let go of some control and are patient about the time it takes, consider an established traditional publisher.

As you make your decision, pay attention to how the publishing and bookselling industry is changing. More people are shopping for and buying their books online, as opposed to in bookstores than ever before. Many also prefer e-books, which is why we were sure to have our book converted to Kindle. Book buyers are making decisions based on word-of-mouth marketing, price and convenience, more than the name of the publisher. If you have a great marketing plan, strong social media presence and a good reputation in your field, self-publishing may be for you.

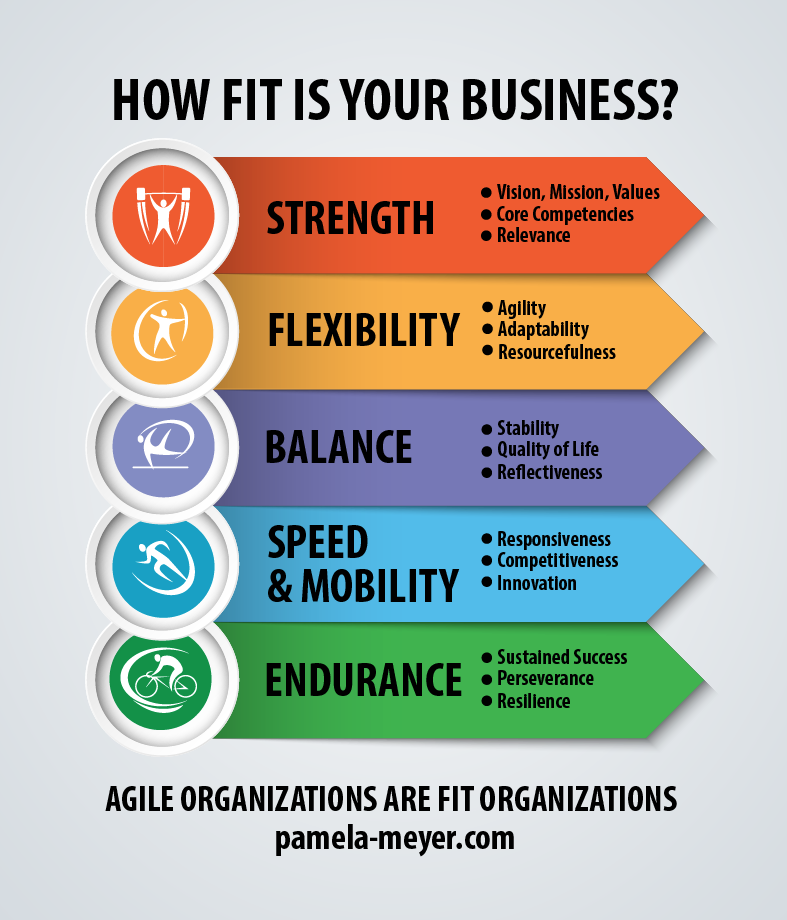

Have you developed the competence and capacity to adapt when things don’t go as planned?

One of the best ways to improve collaboration and flexibility only takes a few minutes. Try it the next time you meet with your team. Kick off your meeting with a quick improv or agility exercise, here is one of my favorites.

One of the best ways to improve collaboration and flexibility only takes a few minutes. Try it the next time you meet with your team. Kick off your meeting with a quick improv or agility exercise, here is one of my favorites.